Do the photographs, paintings or flags in a courthouse or jury deliberation room affect how a case is decided? That question led to the reversal of a criminal conviction in Tennessee, part of the ongoing discussion of race, racism and implicit bias that continues in the criminal justice system. And that reversal was based in part on psychological research – proof that a negative image can create negative responses to an accused.

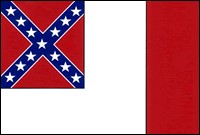

What was the image? It is the “blood stained banner,” the third flag of the Confederacy. It looks like this.

Where was it displayed? In “a room in the Giles County Courthouse maintained by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (“U.D.C.”) and adorned with various mementos of the Confederacy…” State v. Gilbert, 2021 Tenn. Crim. App. LEXIS 550, *2. Those included a portrait of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy.

In dispassionate language common to court rulings, a new trial is required because “the Confederate memorabilia in the jury room was extraneous information and…the State failed to rebut the presumption that the petit jury’s exposure to that extraneous information was prejudicial.” Id. But the Tennessee court did go further, rooting its decision in cognitive psychology by citing legal precedent as to the power of a symbol to affect thinking. “’The use of an emblem or flag to symbolize some system, idea, institution, or personality, is a short cut from mind to mind.’” W. Va. State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 632, 63 S. Ct. 1178, 87 L. Ed. 1628 (1943). State v. Gilbert, at *53.

That flags and photographs do shape thinking and ignite biases is not merely the guesswork of a Supreme Court opinion. It is an acknowledgement with strong scientific support. That science was brought to the Tennessee court’s attention in the amicus brief filed by the Tennessee Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (TACDL). The studies were described by amicus as follows:

Dr. Joyce Ehrlinger then of Florida State University completed two studies on the impact of exposure to the Confederate flag on human behavior. Ehrlinger et al., How Exposure to the Confederate Flag Affects Willingness to Vote for Barack Obama, Political Psychology 32(1) (2011). In the first study a politically diverse group of students at Florida State University were exposed either to the Confederate flag, or a neutral control, and then asked about their willingness to vote for four then candidates for President: Hillary Clinton, Mike Huckabee, John McCain, and Barack Obama. Id. at pp. 135-37. White students exposed to the Confederate flag were significantly less willing to vote for Barack Obama than white students who were not exposed to the flag (while their support for McCain and Huckabee was unchanged, and their support for Clinton marginally increased after exposure to the flag). Id. at 137-139.

In Ehrlinger’s second study, the all-white participants were asked their opinions of a fictional Black man, “Robert”; half of the participants were primed with the Confederate flag, half were not. Id. at 141-42. In the story, Robert refused to pay his rent until his landlord repainted his apartment, and demanded money back from a clerk; after reading the story the participants were asked to evaluate Robert. Id. at 142. Those participants who read the story while being primed with the Confederate flag rated Robert significantly more negatively than did those participants who were not exposed to the flag. Id. at 142-43. Importantly, the participants’ negativity was independent of pre-existing levels of prejudice—people expressing non-discriminatory views still viewed Robert more negatively if exposed to the Confederate flag. Id. at 143.

In both studies the students’ exposure to the Confederate flag was brief. In the first study it was displayed on a screen for 15 ms (15/1,000 of second), id. at 135; in the second study a folder with a Confederate flag sticker was “accidentally left” on a corner of the desk where the students took the examination. Id. at 142.

Ehrlinger concluded that “Our studies show that, whether or not the Confederate flag includes other nonracist meanings, exposure to this flag evokes responses that are prejudicial. Thus, displays of the Confederate flag may do more than inspire heated debate, they may actually provoke discrimination.” Id. at 144.

State v. Gilbert, M2020-01241-CCA-R3-CD, Brief of Amicus Curiae Tennessee Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, 32-33.

Because the case was about the impact of visuals, it is best to conclude this column with two additional ones. First are the graphs from the Ehrlinger article, which starkly show the findings.

the second comes from the Amicus brief. TACDL included more than 20 photographs of American acts of racism and terror, in many of which the confederate flag was displayed. Included was this one from the ‘unite the right’ rally:

We all know that visuals aid in story-telling. TACDL ‘showed’ its story, in that way achieving a “short cut from mind to mind.” And science showed that how jurors think and respond can be starkly influenced by a picture on the wall – a lesson for all of us.

[Thanks are due to Tennessee attorney Evan Baddour, who saw this issue and litigated it and then kindly provided the briefs to this writer. Mr. Baddour graduated from law school in 2018. ttps://www.baddourlaw.com/colby-baddour/evan-baddour]