If I were a true believer in the power of unanswered rhetorical questions the rest of this column would be blank. Or maybe not; because maybe the power of the question comes when it follows compelling information that guides the audience to the desired response. So – let me provide the information and then see whether the question, indeed, answers itself.

First, where did the question come from? The book CLOSING ARGUMENTS & THE P.E.R.M. SYSTEM (Win Big. More Often) by Jim Garrity maintains that a successful closing has but four elements:

- Pathos (Passion)

- Eye Contact

- Rhetorical Questions

- Metaphors

Before I go on, a disclaimer is needed. I don’t know Mr. Garrity, I stumbled on his book, and I found it cited only once in a LEXIS search. But Garrity professes to have conducted “two years…[of] academic and psychological research…” and begins his book with ample citations to resources for each of his elements. For rhetorical questions, he cites 12 authorities across a number of disciplines. That seemed to be a solid foundation to read further.

What does Garrity urge? The gist is simple:

Rhetorical questions are integral to the PERM system for one reason: They are as close to an actual conversation you can have with your jury. Rhetorical questions force jurors to engage with you. The jurors will answer your questions, albeit silently, but that is good enough. A century of psychological research shows that it is nearly impossible for a passive listener to avoid answering a rhetorical question.

CLOSING ARGUMENTS, 2.

There is at least one more aspect to Garrity’s approach. He reasons that jurors are in some sense “low-involvement” audience members as the case outcome will not impact them, and then explains that “[a] juror who is not naturally inclined to process your message is more likely to do so if you include rhetorical questions in your message presentation.” CLOSING ARGUMENTS, 37.

Garrity suggests a variety of forms of rhetorical questions:

- ones that require a one word answer (Garrity’s example – “Did Mr. Williams bother to read the contract”);

- ones that require a multi-fact answer, but with those facts listed after the question is posed (Garrity’s example – “Just how hard did Sally Davis work to resolve this before coming in this courtroom,” followed by “let’s look at the facts); and

- ones that are a tag line to an assertion (Garrity’s example – “You heard that Ms. Williams did absolutely nothing to help Christopher Edwrads after she struck him and saw him lying there, dying. Why? Why?”).

So, that is Garrity. What about trial advocacy texts? A survey of several showed ran the gamut of possible responses:

- Lubet and Lore’s MODERN TRIAL ADVOCACY 6th edition mention s rhetorical questions only in regard to opening statements, with a warning that they are “inherently argumentative” and thus inappropriate. MODERN TRIAL ADVOCACY, 416.

- O’Brien and Townes, in TRIAL ADVOCACY BASICS 3rd Edition, give such questions a defense as a “marvelous technique when there is a key question to which you know your opponent has no effective answer. TRIAL ADVOCACY BASICS, 251.

- Perrin, Caldwell and Chase, in THE ART AND SCIENCE OF TRIAL ADVOCACY, 2nd Edition, urge use of rhetorical questions as, when “used effectively, the advocate controls the conclusion that the jury will draw, yet allows the jury to feel empower, as if they reached that predetermined conclusion on their own.” ART AND SCIENCE, 449.

- In the classic THE WINNING ARGUMENT, JoAnne Epps and colleagues describe rhetorical questions as “an excellent way to lead the listener [and]…cause your listener to …form conclusions that he can embrace as his own. WINNING ARGUMENT, 155.

Other advocacy texts have little or nothing.

[An interesting aside. There has been some positive discussion in the legal writing community of using rhetorical questions in brief writing and oral argument. See generally, Simon, The Power of Connectivity: The Science and Art of Transitions , 18 LEGAL COMM.. AND RHETORIC 66, 73 (Fall 2021) https://www.alwd.org/lcr-archives/fall-2021-volume-18/621-the-power-of-connectivity-the-scien%20ce-and-art-of-transitions .]

A survey of our advocacy community produced a myriad of responses, and they are appended to this article. The ‘big picture’ is as follows: out of 23 respondents, 20 were favorable and 3 were not. An interesting theme across both ‘camps’ was that such questions are dangerous if counsel does not also provide an answer.

Our colleague Gary Gildin, extremely knowledgeable about neuroscience, penned a cautionary note:

From a brain perspective, the challenge for closings in general, and rhetorical questions in particular, is how not to undermine the success we already achieved by the System 1 persuasive force of our trial story by forcing the jurors to engage in System 2 evaluative thinking. Done properly, the opening statement told a story that the jurors’ brains automatically and subconsciously found to be the best match to their life experience. Having found the satisfactory answer without unnecessarily wasting glucose, for the balance of the trial the jurors’ brains welcomed evidence that confirmed their decision and ignored—in fact, actively suppressed—contradictory evidence.

The last thing we want to do in closing is to induce the jurors to surrender their existing conclusion by prompting them to carefully consider and evaluate competing evidence. At the same time, we do not want to sacrifice the opportunity to argue the flaws in the opposing side’s factual story and the credibility of their witnesses. My current view is that the imperfect– but best available—option is to first argue the flaws in the opposing case, ending with the transition “why do these problems exist? Because that is not what happened.” We then pivot to an uninterrupted, System 1 aligned recounting of our factual story of the case.

Rhetorical questions, in my view, are a System 2 tool. Therefore, I would use rhetorical questions only for specific evidence or witnesses in the Part 1/flaws in the opposing case section of my closing. I would stay wholly in storytelling mode for Part 2 of the closing, the reiteration of our story. I suppose my proposed transition is itself a rhetorical question, one I would wholeheartedly endorse.

I asked our librarians at Temple Law to help update the research. There was not much new, and certainly nothing that undercut Garrity’s thesis. One article gave the issue an added facet – asking questions increased listener perception of the speaker’s receptiveness.

A person who makes declarative statements (e.g., “this new policy will boost productivity”) could be seen as more firm or assertive than someone who phrases the same position as a question (e.g., “won’t this new policy boost productivity?”). By implicitly inviting input, a source who asks questions might be seen as more receptive to others’ views.

Hussein, M. A., & Tormala, Z. L. (2021). Undermining Your Case to Enhance Your Impact: A Framework for Understanding the Effects of Acts of Receptiveness in Persuasion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 25(3), 229-250. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683211001269 (Original work published 2021)

Let me link this to a related issue – reactance theory. This was explained in a review of the book PERSUASION SCIENCE:

People are usually more convinced by reasons they discovered themselves than by those found out by others. By enticing the jurors to fill in the missing information, they will reach the desired conclusions. If you tell them, they will resist; but when they arrive at their own conclusion, it sticks because they have persuaded themselves.

Persuasion Science, 56. Imagine a closing argument where the advocate does not say “the evidence demands a finding of…” but instead hands that to the jurors with a soft “could those be the result of carelessness…?”

This lesson is part of a broader one about “reactance.” The author explains this in detail, with a personal experience driving it home:

Reactance is the resistance to something that is perceived as a threat to one’s autonomy or freedom of choice. Words like “must,” “should,” and “need” are known reactance triggers. I learned this lesson during a mock trial. I was going through the verdict form and told the jurors how the questions should be answered. I had noticed that a young woman juror was paying close attention. I thought that I must have been very persuasive. Shortly afterward, while I observed deliberations on a remote monitor, I was stunned when she said, “Can you believe that douchebag plaintiff lawyer telling us what to do?”

Persuasion Science, 91.

https://law.temple.edu/aer/2022/10/24/persuasion-science-for-trial-lawyers/.

PERSUASION SCIENCE is not the only source confirming the validity of reactance theory. In THE INFLUENTIAL MIND, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience Tali Sharot posits that:

In order to affect another person, we need to overcome our own instinct for control and consider the other’s need for agency. This is because when people perceive their own agency as being removed, they resist. Yet if they perceive their agency as being expanded, they embrace the experience and find it rewarding.

Id. at 84-85.

Admittedly, not every urging by counsel will provoke a reactance response. Some research looks at whether there is a “message that is perceived as highly threatening to one’s freedom…” Steindl C, Jonas E, Sittenthaler S, Traut-Mattausch E, Greenberg J. Understanding Psychological Reactance: New Developments and Findings. Z Psychol. 2015;223(4):205-214. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000222. PMID: 27453805; PMCID: PMC4675534.

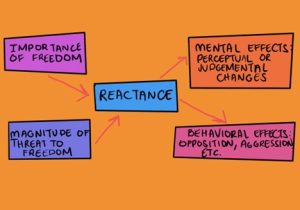

This image attempts to capture the reactance phenomenon:

https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/psychology/reactance-theory (last visited August 6, 2025).

So, where does this leave us? I won’t tell you to use rhetorical questions that you let the jury answer on their own – the reactance to that domineering mandate will preclude your considering it. And I do take to heart the concerns many of you articulated about leaving the jury unguided on certain issues, and especially take to heart Gary Gildin’s neuroscience approach.

But – and if it isn’t clear I am telling you that this is my rhetorical question – aren’t there some cases where it is safe and smart to say to the jury “did they have to drive that fast” or “couldn’t – and shouldn’t – they have done better?” Is it time to try this?