The Hollywood lawyer – whether Gregory Peck, Kate Hepburn, Paul Newman or Denzel Washington – never speaks from notes. And Cousin Vinny, although he never had to give a closing, certainly had no paper in hand when he delivered his inimitable opening statement of “everything that guy said is [expletive deleted].” But it is the rare lawyer who has spoken without notes and then not thought “darn, I wish I’d remembered to say that.”

Whatever Hollywood and television have done to shape audience perceptions, there is no reason to conclude that audience expectations are that an attorney will never use notes (except in student mock trial competitions), or that an attorney who does so somehow has diminished credibility or effectiveness. Given the edict that preparation is key to success in advocacy, or as words attributed to Abraham Lincoln explain, “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe,” reliance on memory, that incredibly faulty and distractible tool, is a less than desirable approach.

Consider this summary of ‘brain science’ offered by the American Psychological Association as it refers to memory and recall abilities:

The brain’s volume peaks in the early 20s and gradually declines for the rest of life. In the 40s, when many people start to notice subtle changes in their ability to remember new names or do more than one thing at a time, the cortex starts to shrink…The normally aging brain has lower blood flow and gets less efficient at recruiting different areas into operations. – American Psychological Association, “Memory Changes in Older Adults“

The correspondence between decline in memory and the age of the average graduating law student – 27 – counsels heavily against a closing (or any other aspect of trial) being conducted without notes of some sort.

So two questions arise – what type of notes, and how to do this effectively to ensure not only a comprehensive and accurate presentation but one that jurors will respond to affirmatively, if not embrace?

To answer this I turned first to trial advocacy textbooks to see whether the issue of using notes was discussed, and if so what the advice was. The strongest endorsement comes from Steven Lubet, who asserts that “[t]he most effective final arguments are those…delivered from an outline[,] as this allows planning, delivery “with an air of spontaneity,” and nimble response to the opposition’s points. – Lubet, MODERN TRIAL ADVOCACY, LAW SCHOOL 3RD EDITION, 391.

Thomas Mauet is more circumspect, endorsing notes but urging that they be modest if not minimal because extensive notes “remind the jurors that what you are saying has all been planned” and may “deaden the delivery” at a time “where passion and commitment count.” – Mauet, TRIALS, 2ND Edition, 476.

Berger, Mitchell and Clark urge having an outline “near a cup of water so that you can take a sip and glance at them.” – TRIAL ADVOCACY: PLANNING, ANALYSIS AND STRATEGY, 2ND EDITION, 543. And even 80 years ago, Irving Goldstein opined that “the argument should be planned in advance (not memorized)” and “a definite outline should be made…” – TRIAL TECHNIQUE, 613 (emphasis added), 616. Surprisingly, only one major advocacy text, Charles Rose’s FUNDAMENTAL TRIAL ADVOCACY, is silent on the issue, focusing on content of closings rather than delivery.

And practitioners? In a random survey of judges who previously were trial lawyers and of practitioners there was near consensus – with two dissenting voices – that notes/outlines are essential. The comments were so thoughtful and depictive that they are included (albeit anonymously] in great detail at the conclusion of this article. The shared emphases are: make them short, easily readable to you and not a distraction to the jury; make particular use of them when quoting a document or testimony; and otherwise don’t read your speech, give it.

Indeed, one can embrace the use of notes. After a note-free beginning, acknowledge that “you see I am using notes. Sorry, if Hollywood or TV made you expect otherwise. But this case is too important to X, and accuracy is what you are entitled to, so please bear with me.” As one poll of jurors concluded, “Veracity and humility were the character traits which went over well with jurors.”

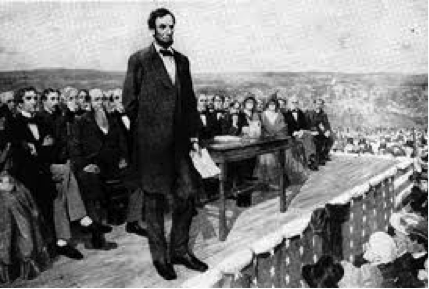

But can it be done without sacrificing emotion and intensity? The answer comes from Abraham Lincoln. The Gettysburg address was all of 272 words; and if the below painting is an accurate depiction, Lincoln delivered it with notes.

Practitioner Comments Regarding Using Notes

+ I did use notes but did it in an odd way. I would write an outline on the [courtroom white] board and let it serve 2 purposes (1) it helped me stay organized and hit the key facts and (2) jurors saw it and to the extent people believe what they see in writing then it worked. I found it to be helpful to the jury. When I opened the white board they visibly turned in their seats to engage with my “notes”. I did also then take a picture of the board for the appeal.

+ Notes are Ok to reference bullet points – don’t carry them around the well of the court leave them on lectern go to them on an as needed basis.

+ I like a PowerPoint.

+ I DO use notes and I know that many people think we should not. Here are my responses: Always. Because there are always crucial issues that must be included in the closing, and I am not full of myself enough to be sure that I’ll remember to include them in the heat of the moment if I don’t have notes. Also, in some cases it’s crucial to word something a particular way, and I’ll make sure I have it written down so that there’s no risk of flubbing it (consider, for example, some of the critical burden of proof and weighing issues in a capital sentencing closing).

Put the notes on the lectern and use them when you need to do so. I tell law students that it is always more effective to read well than to try to speak without notes and do it poorly. President Obama delivers a pretty good speech when he reads (and he almost always does), so I’m convinced it can be done!

I have never heard that it is a distraction or a turn-off. When I talk with jurors, they spend almost all of their time talking about what they understood the evidence and issues to be, not what they thought about the presentation styles. Obviously, things are not so simple – the latter has a real impact on the former. But I think that the way jurors express their impressions at least suggests that they did not find my methodical, tedious reliance on notes to be a turn-off.

+ I find that notes are not as necessary as folks tend to believe that they are. There are teachable techniques that permit an attorney to give a comprehensive speech (opening or closing) without using a single note.

On the other hand, notes do not have to detract from the closing, if the attorney puts some effort into creating a usable format. In other words, don’t use a written out text. Use single words or phrases in very large font. Stop talking while you are looking down at your notes and use the silence to your advantage.

Don’t lock yourself into a lectern (unless you have to); put your notes in the most accessible spot that you can, so that you can glance at them without too long a silence.

Finally, rehearse your closing at least three times (aloud, if you can) and use different words each time. Your goal is NOT to memorize, but to simply get comfortable with the logical progression of your argument.

+ I don’t use notes but I use powerpoint, which in my mind fulfills the purpose of notes but avoids the negative of constantly looking down. Before I used powerpoint, I did use notes. Basically, it would just be an outline, sort of a powerpoint presentation that I did not project.

I think notes can be used effectively if they are not used as a crutch. Notes need to be an outline or a framework and not a script. If they are used that way I think it’s fine. If it’s just an outline you aren’t constantly looking down, only occasionally so to figure out where you are and what the next point you want to make.

Again, I think it is a turn off if it’s a constant looking down and not making eye contact. If someone giving a long closing argument has to pause a few times to look at an outline I think that’s fine. I think it can be a positive in terms of making sure the closing is well organized and flows well, so it can be a help as long as the notes are truly notes and not a script.

+ As a trial lawyer, I used a one sheet outline, plus a legal pad which I’d flip through a couple of pages to say to the jury: “Now, let me tell you exactly what the witness said….”

As a judge, the best use of notes I ever observed was an attorney who, at the beginning of closing, said: “Now I want to apologize for using notes, but this case is my client’s future, I’m nervous and I don’t want to miss a single important thing.”

+ I don’t use notes. I want to engage with my jurors and looking down at notes breaks this engagement. By the close of the case, or by the beginning for that matter I should know my facts and the arguments I want to make well enough to talk about the case without notes.

Can it be done effectively? How? Probably not. However, IF I am afraid of forgetting a particular point I want to make I have placed a piece of paper with a short list of the points I want to make on counsel table. I have a co-counsel or sometimes my client check off each of the points as I make them. When I am at the very end of my closing I will walk over toward counsel table, glance at the list and make sure all the points are checked before concluding.

Is it a turn-off to or distraction for jurors or otherwise a negative? I think it is a distraction. Engaging with jurors and making eye contact is very important and powerful. The worst example I have seen is someone, who was using notes started by saying “my client is not guilty” paused, looked down and read “because.” The danger of this kind of thing happening and sending the wrong message to jurors can have a more devastating effect that forgetting to make one little point you meant to talk about.

+ Notes are not the issue; the issue is whether the attorney simply reads the notes. Notes are effective reminder of key phrases, or a vehicle to make sure all points are covered in a logical manner (e.g., outline).

+ I do use notes, and I have used some lengthy and detailed notes before in complicated murder cases that took weeks to try and that I closed on for well over an hour, but more often then not I usually work off a short, written outline that I try to confine to a single sheet on a legal pad. It helps me to present an organized and logical argument and (hopefully) not miss any of the points I want to make to the jury.

I just keep the pad on my table and then refer to it as needed during my closing argument. I prefer to use a legal pad because it’s more sturdy than a piece of paper such that I’m able to pick it up and hold it with one hand and move around with it if necessary, but it’s not as bulky as notes in a 3-ring binder, and the jurors are already used to seeing me use a legal pad during the trial. The outline mostly consists of key issues and arguments regarding the evidence and the law in the form of simple bullet points, and it’s usually organized in the same manner: 1) my evidence/case; 2) my response to defense arguments; and 3) my argument on the law that applies in the case. It’s much like how one would use PowerPoint slides for a presentation. You don’t just read the slides, but rather you use each slide to make a point and to keep you focused and organized. In fact, I’ve even seen some lawyers use PowerPoint slides during their closing arguments in lieu of written notes, and I thought it was very effective.

The plus for me in using notes is if I go off on something that suddenly occurred to me while I’m talking I can always go back to my outline and not lose my place or forget what I was talking about or miss a point entirely. The minus is if I were to stick entirely to my notes I may lose an opportunity to be creative and make other points that come to me when I’m “in the moment”.

As long as you’re not just reading your closing argument from your notes I don’t think using notes during a closing argument is a distraction for the jury. The idea is to try and connect to the jury and get their attention, and then give a closing argument that is both compelling and persuasive trying only to use your notes as a source of reference for each of the points and arguments that you want to make to the jury without letting your notes become a distraction.

+ On your closing notes inquiry, I always used notes by way of a general outline with bullet points, sort of idea topics to follow. Never more than 2 pages of bullet points. Helps organization, assists in remembering all points you want to make, especially in complex case. Of course never read notes. Jurors don’t mind use of notes if it helps you to stay organized and notes are only used as an aid.

+ I would use a one page note at closing with key words to keep me on the topics in correct order. I think it can be done effectively as long as you don’t pick up the page and review it in front of the jury. I would study the paper the night before closings and the next morning also. As long as the jurors aren’t distracted I don’t think it is a turn-off or a distraction.

+ Notes are perfectly acceptable. Reading your closing is not. The most important thing is giving a reasoned articulate compelling closing. Virtually all of the best trial lawyers I have watched use either notes or some sort of an outline