The US Feminist Judgments Project brings together feminist legal theorists, practicing lawyers, clinicians and legal writing professors of diverse backgrounds and experiences to rewrite influential United States Supreme Court opinions about gender-related issues using feminist reasoning and analysis. Far from an academic exercise, the Project aims to show the practical – and powerful – impact that feminist theory can have on the law. We sat down with co-editor Professor Kathy Stanchi to learn more about the Project and what she hopes it will accomplish.

TLS: What was the inspiration behind US Feminist Judgments? How did the idea come into being and how did it grow from there?

KS: The idea first came up in 2013, when I heard a British scholar named Erika Rackley present at the Applied Legal Storytelling conference in London. Erika was the co-editor of Feminist Judgments, a U.K.-based project in which scholars used feminist legal theory to rewrite significant decisions in U.K. law. I realized that U.S. law was more than ripe for similar treatment. We wanted to draw on the entire body of feminist legal theory and show its broad, practical applications. While there’s been a movement over the past decades toward impact litigation that incorporates feminist arguments, we haven’t seen feminists actually showing how legal decisions could have been decided differently – yet.

So I and my wonderful co-editors, Bridget Crawford and Linda Berger, decided to limit our scope to decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court, based on its influence, its status as the court of last resort, and the degree of freedom provided to the Justices when they author opinions. We further limited our work to cases about gender or women’s rights, recognizing that future projects can and should address other courts and areas of law. Even with those limitations, we were looking at well over 60 to 70 cases! Our Advisory Panel helped us make some tough choices, and eventually we were able to arrive at the final roster of 25 cases. We then put out a call for contributors, and were fortunate to have well over 100 people express interest in writing for the book.

TLS: The book is being published by Cambridge UP and has already attracted notice from some influential legal observers, including SCOTUSBlog and the ABA Journal. It’s safe to say that the Project is a pretty big deal. Why do you think there’s so much interest in this topic at this time?

KS: I think that the interest in this project is directly tied to its practicality and its innovative approach. We are trying to show how law could have been different. All our authors are required to use the precedent that was in place at the time of the decision. That guideline seeks to show that many decisions may not have been driven as much by stare decisis as by the biased cultural views of the judges. I feel like this project epitomizes why it is so important to have diversity in the judiciary – especially diversity of perspective. Justice Sotomayor famously said that a “wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences” would make different and better decisions than someone without those experiences. Our project aims to show that judicial opinions as a body have not necessarily been written by judges with the widest range of life experiences – leading to systemic inequalities based on race, gender, sexuality and class. These systemic inequalities are not intrinsic to law and can be changed. I hope the project proves that change is possible.

KS: I think that the interest in this project is directly tied to its practicality and its innovative approach. We are trying to show how law could have been different. All our authors are required to use the precedent that was in place at the time of the decision. That guideline seeks to show that many decisions may not have been driven as much by stare decisis as by the biased cultural views of the judges. I feel like this project epitomizes why it is so important to have diversity in the judiciary – especially diversity of perspective. Justice Sotomayor famously said that a “wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences” would make different and better decisions than someone without those experiences. Our project aims to show that judicial opinions as a body have not necessarily been written by judges with the widest range of life experiences – leading to systemic inequalities based on race, gender, sexuality and class. These systemic inequalities are not intrinsic to law and can be changed. I hope the project proves that change is possible.

TLS: How do you respond to criticism characterizing projects like this as speculative or impractical?

KS: Two thoughts come to mind in response to this question. First, as I noted, the authors had to use the law and precedent in place at the time of the decision. They were also not allowed to cite theory that had been produced after the opinion. The idea was to show that the cases could have been decided differently using feminist thought within the bounds of stare decisis.

Working under these constraints, our authors reported an interesting phenomenon -the feminist points they wanted to make were already in the amicus briefs or otherwise present in the discourse at the time. This was even true in our oldest case, Bradwell v. Illinois, which was decided in 1873. We simply haven’t given enough credit to the early feminists, who were very much out there making these arguments that got carved out of legal history. So the project is in no way speculative- if anything, it’s recovering an important piece of our shared history.

The second thought is about how that piece got lost in the first place. One of the goals for this project was to challenge the idea that these opinions were written from a neutral vantage point – one that was inexorably logical, and in fact the only logical path possible. It’s simply not true. Rather, these opinions were uniformly grounded in cultural bias, meaning that uncited cultural and social beliefs privileging a certain gender or race or sexuality were allowed to pass for law and ended up driving the opinions. For example, in Dothard v. Rawlinson, the Court upheld a regulation barring women from working as correctional officers in a male maximum security penitentiary. The Court’s reasoning is based on the uncited view that the mere presence of women could incite the prisoners to attack or sexually assault them. In other words, women cause rape by their very presence, their very “womanhood,” in the words of the majority. There was no supporting evidence for that assertion – it was merely the Justices’ beliefs about women, men and rape passing for law and legal reasoning. And once the Supreme Court wrote that, it made one of the most enduring and damaging rape myths into the law of the land. It reified that view of rape and women and erased from the law the competing feminist perspective.

TLS: What, besides exposing hidden gender bias, do you think feminism has to offer the law as an institution and as a profession?

KS: It was very important to the editors of this project to be not just about gender bias, but also about racism, homophobia, classism and transgender issues. We are all committed to a “big tent” feminism with room for multiple feminisms within. We wanted the history of racism/sexism intersectionality to be a part of the book, and we made a concerted effort to have multiple points of view represented throughout. The authors are diverse by race, sexuality, and gender. They are practicing lawyers and law professors of diverse statuses and different levels of seniority. We believe that feminism belongs to everybody; at its best, it is a social justice project on many levels, not just for women.

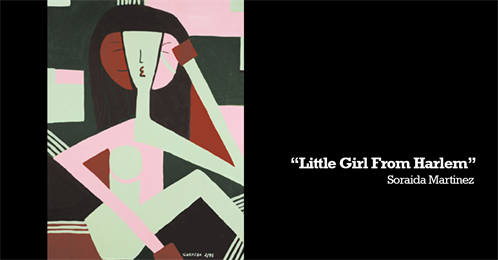

That’s why we chose the painting by Soraida called Little Girl from Harlem, pictured above,for our website and have recommended it for the cover of the book. Soraida is a Latina artist who pioneered the art style of Verdadism, a unique and thought-provoking style that addresses issues of sexism, racism and stereotyping by combining painting with social commentary. We thought that Soraida’s message about the beauty of diversity was right in line with how we saw our own project.

The US Feminist Judgments Project is slated for publication in Spring 2016 by Cambridge University Press. For more information about the Project, including cases and contributors, please visit the Project website at http://sites.temple.edu/usfeministjudgments/ and follow the Project on Twitter (@usfemjudgments).