Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS): Accountability, Collateral Damage, and the Inadequacies of International Law

By: Miron Sergeev, LAW ‘26

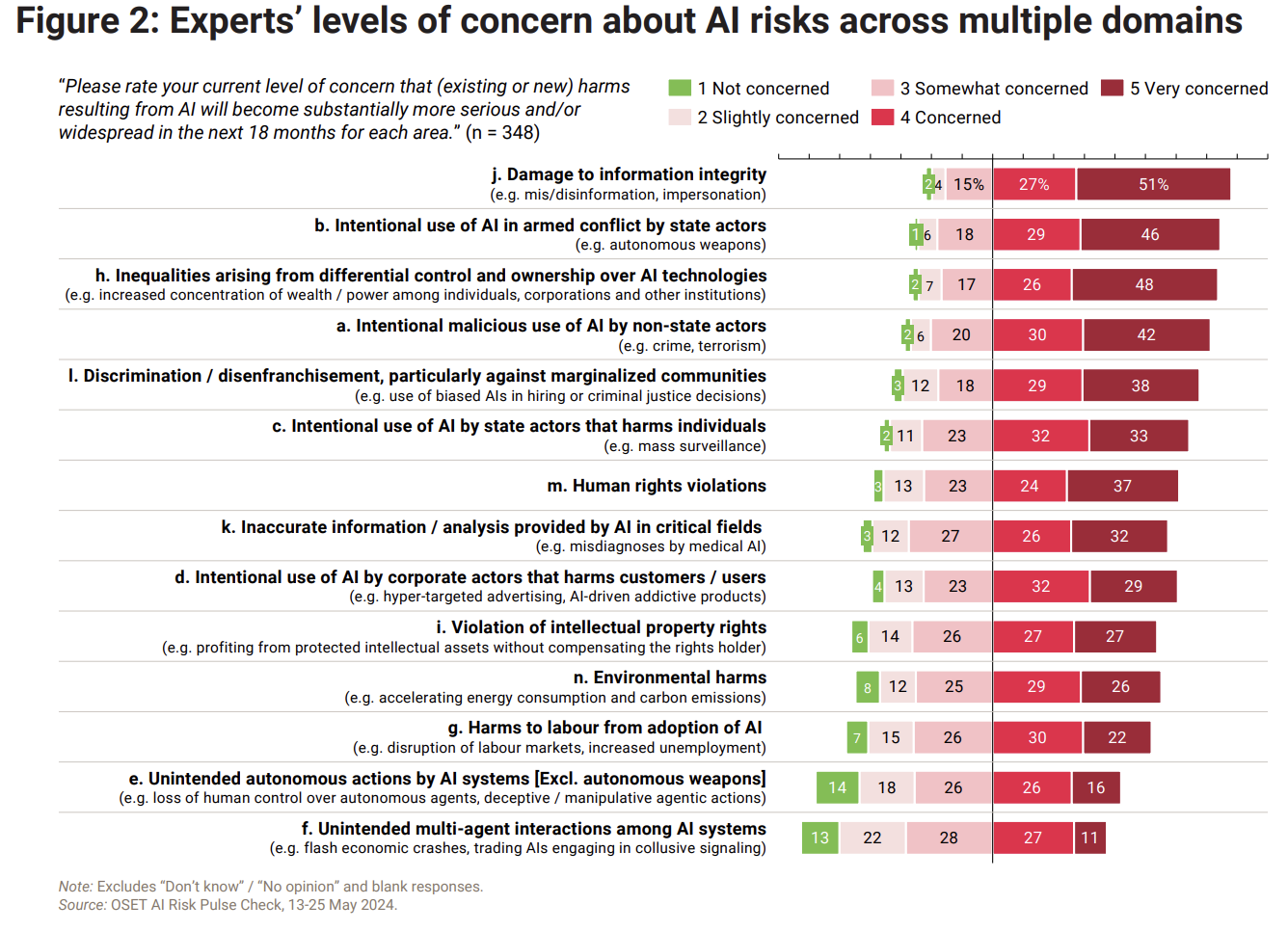

In a time of escalating conflicts across multiple continents and the rapid deployment of new weapon systems relying on artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and other emerging technologies— is international law up to the task of regulating the conduct of war and holding states and non-state actors accountable? How should individuals answer for crimes committed on a mass scale using autonomous weapons? Where should the line be drawn between lawful behavior and breach of state responsibility? One thing is clear: the international community must face the reality that autonomous weapon systems do not fit within the paradigm of conventional weapons covered by existing international law.

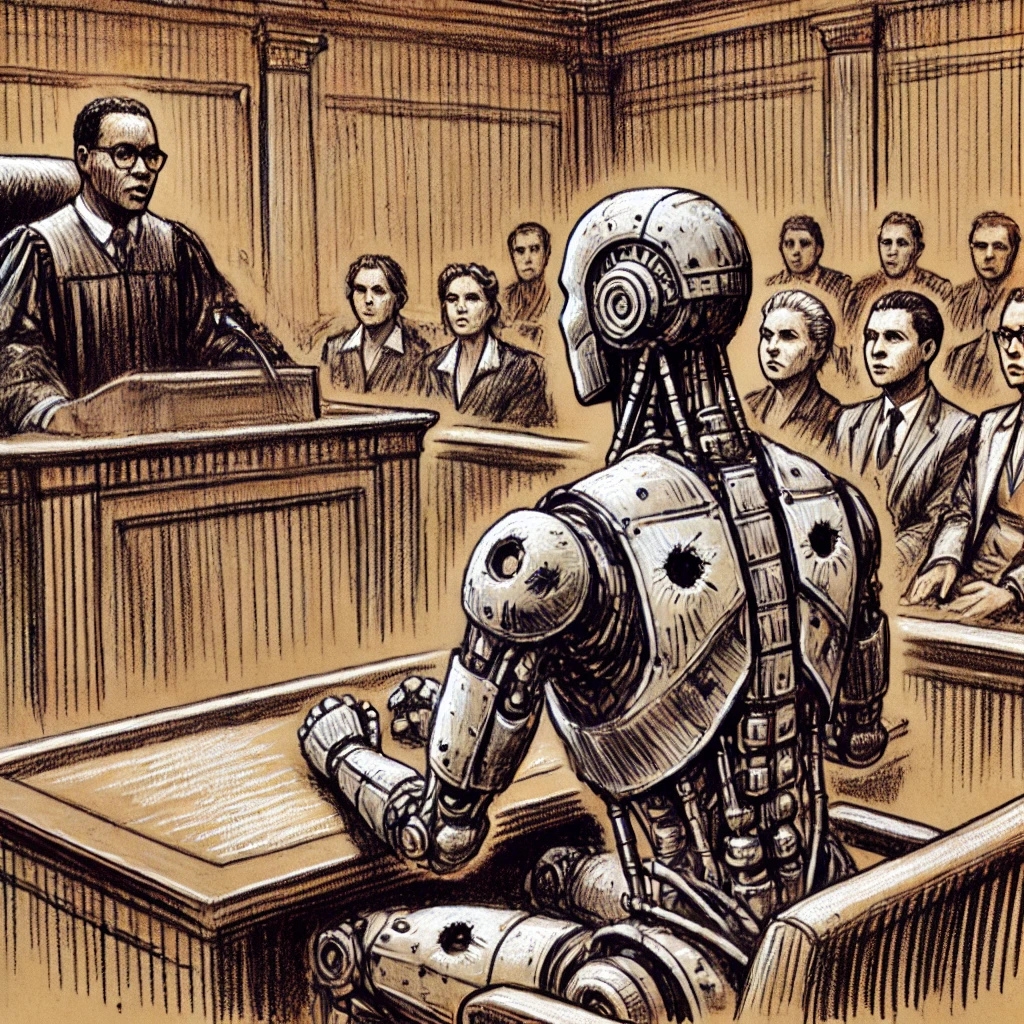

Deployment of LAWS & Excessive Harms to Civilians: Russia-Ukraine War

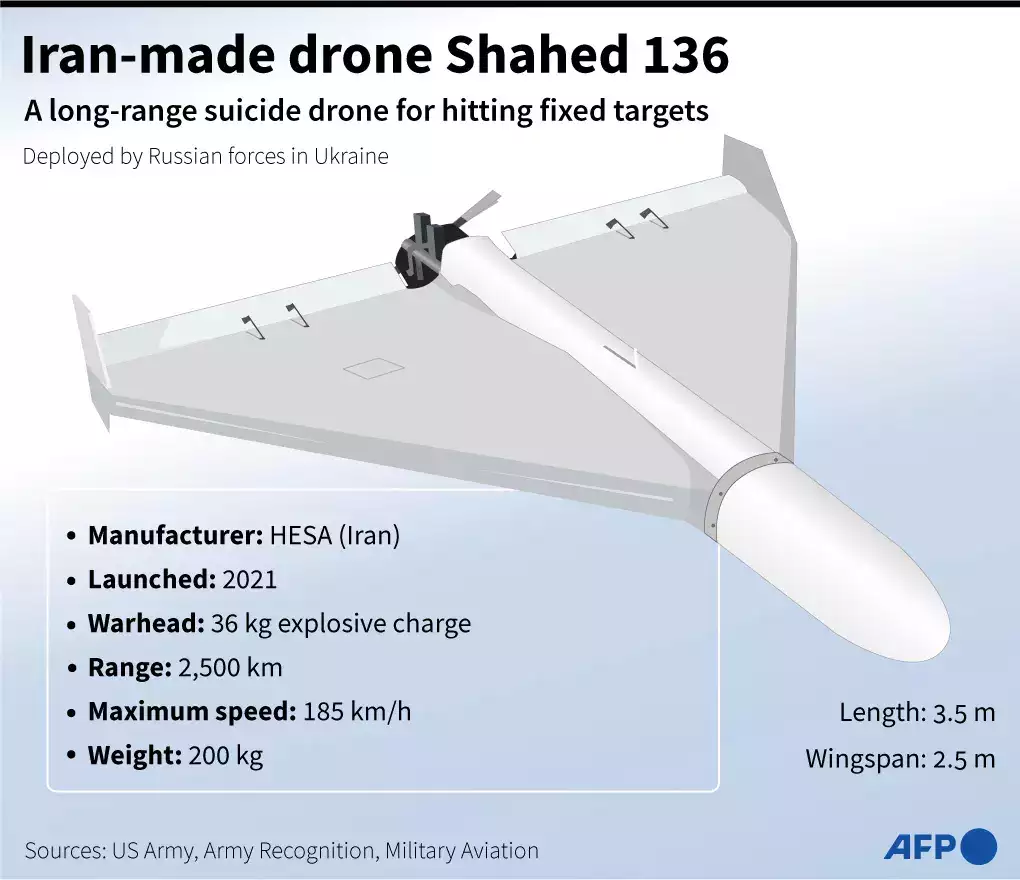

In December 2022, hundreds of self-detonating drones bombarded energy infrastructure in Ukraine. Swarms of Shahed-136 drones autonomously patrolled the skies before launching themselves in large waves at the power grid. Two energy facilities in the city of Odesa were annihilated by these autonomous explosive devices, leaving 1.5 million people without access to electricity and heating in the coldest months of winter.

The dominant force in the European theater of war deployed by the Russian Federation is the Shahed-136, a suicide drone capable of annihilating energy infrastructure and injuring millions of civilians. Suicide drones or loitering missile systems, such as the Shahed-136, are autonomous weapon systems, as they are intended to engage individual targets or specific target groups that have been pre-selected by a human operator. The Shahed-136 is classified as a Lethal Autonomous Weapon System (LAWS). Once activated, such systems can independently identify and destroy a target without manual human control or further intervention by a human operator. Moreover, advances in AI expand the technical scope of LAWS and enable them to autonomously kill by relying on sensor suites and computer algorithms that expedite machine decision-making.

Multilateral efforts to regulate LAWS have been underway in the United Nations for a decade and state backed frameworks aimed to build international consensus for responsible behavior and use of LAWS—such as the Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy—are gaining support. However, a serious accountability gap in international criminal law remains, as evidenced by deployments of such weapons in armed conflicts, including the Russia-Ukraine war. There is a pressing need for an obligatory framework of international law to govern autonomous weapon systems and improve the protection of human rights. As technologies like killer robots inexorably develop, the law of armed conflict and mechanisms of criminal accountability should be updated to deter the losses produced by a weapon system relying on any level of autonomy. The mere adaptation of the current framework that regulates conventional weapons is insufficient to combat the challenges presented by modern war technology. New rules must be developed to restrict the development and deployment of autonomous weapon systems.

History & Development of Autonomous Weapon Systems

Fully autonomous weapon systems differ from traditional guided munitions, which are technically semi-autonomous weapons. Historically, many “fire and forget” weapons, such as certain types of guided missiles, delivered effects to human-identified targets using autonomous functions, but they at least include a “human in the loop.” As early autonomous weapon systems developed, the category of “human in the loop” design emerged, describing systems in which the operator can monitor and halt a weapon’s engagement. Fully autonomous lethal weapon systems, however, are essentially software-enabled, powered machines capable of executing a set of lethal actions by computer control, i.e., killer robots.

In 2013, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions, Christof Heyns, issued an early call to action regarding the human rights and humanitarian risks of LAWS. Since then, lethal autonomous robotics have continued to raise fundamental questions about the law of armed conflict, human rights, and legal accountability. In arguing against taking human decision-making out of the loop, Heyns invoked the Martens Clause, a longstanding, customary rule of international humanitarian law, requiring the application of “the principle of humanity” in armed conflict. Heyns’ report argued that taking humans out of the loop in monitoring target engagement and execution by lethal weapons technology also risks taking humanity out of the loop. Heyns crucially warned that the question of legal accountability may be an “overriding issue,” especially if the interactions between constituent components of modern weapons are too complex for military commanders, programmers, or manufacturers to understand individually, leaving a “responsibility vacuum” and “granting impunity” for all uses of LAWS.

Beginning in 2016, the State Parties to the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) convened a Group of Governmental Experts on autonomous weapon systems to debate the issues. An onslaught of new AI-based technologies quickly revolutionized the debate, as increased computing power, improvements in facial recognition technology, better flight navigation, and other technological advancements in distributed autonomy expanded the state of play. By 2021, autonomous weapons became a military reality as retreating rebels in Libya were “hunted down and remotely engaged by… lethal autonomous weapons systems such as the STM Kargu-2,” deployed as “loitering munitions” which “were programmed to attack targets without requiring data connectivity between the operator and the munition: in effect, a true ‘fire, forget and find’ capability.” While civil society decried the inadequacy of international law to prevent severe humanitarian harm by autonomous weapons, states affirmed the application of international humanitarian law to LAWS, but debated definitions and characterizations, disagreeing on concepts, such as “meaningful human control” and “human judgment.”

The Guiding Principles of the CCW on autonomous weapons include mitigation measures in the design of systems, a prohibition on anthropomorphism, and the recognition of the CCW as an appropriate framework for striking a balance between military necessity and humanitarian considerations. The Guiding Principles are meant to inform restrictions on the use of LAWS which are excessively injurious or have indiscriminate effects. Despite meeting consistently every year outside of the COVID-19 pandemic, the High Contracting Parties to the CCW and the subsidiary GGE merely articulate how existing international law applies, rather than creating new binding rules for LAWS. As the development and deployment of AI-enabled weapons shows no signs of stopping, the United Nations Secretary-General, Antonio Gutiérrez’s 2023 New Agenda for Peace recommends that states conclude a legally binding instrument to not only regulate all types of autonomous weapon systems, but also outright ban LAWS that function without human control or oversight, and which cannot be used in compliance with international humanitarian law. The Pact for the Future urgently advances discussions to develop an instrument through the GGE, whereas the final report on Governing AI for Humanity identifies LAWS as an AI-related risk based on existing vulnerability to health, safety, and security.

While states and high-level expert groups consider the full legal ramifications of AI-enabled warfare, the question of individual or corporate accountability may ripen more quickly as cases reach courts and tribunals.

International Criminal Law: Use of LAWS in War Crimes & Crimes Against Humanity

The Russian invasion of Ukraine involves the tactical deployment of autonomous weapons to destroy energy infrastructure, revealing novel issues of criminal accountability in international criminal law. Criminal responsibility is traditionally first assigned within military ranks, implicating mechanisms of command responsibility to account for abuses of LAWS. The military chain of command that extends from the primary war chief to the lowest soldier cannot permit an order which is illegal under international law. The judgments of the Nuremberg Trials and the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal affirm that commanders are criminally responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by their troops when they fail to prevent or punish the perpetrators. The use of novel military technology to commit mass murder or wreak havoc upon civilian infrastructure does not change the calculus of command responsibility.

Legal accountability for uses of autonomous weapons may also entail other forms of responsibility, including moral blameworthiness (in the form of culpability or fault) on the part of developers, deployers, and operators. The inappropriate use of autonomous weapon systems may constitute a war crime, crime against humanity, or even the crime of genocide under international criminal law, depending on factors such as whether a target group was intentionally destroyed based on ethnicity or a civilian population was systematically exterminated by directed attacks.

Between March–June, 2024, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued a series of arrest warrants against the Russian high command, including the Commander of the Long-Range Aviation of the Aerospace Force, Sergei Kobylash, the Minister of Defense, Sergei Shoigu, and the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, Valery Gerasimov, for the war crimes of directing attacks at civilian objects and causing excessive incidental harms to civilians. The evidence justifying the arrest warrants indicates that these members of the Russian high command bear responsibility for missile strikes against Ukrainian electric power plants and substations from October 2022 to March 2023. Russian units organized waves of Shahed-136 drones, which flew circuitous routes programmed to autonomously destroy power plants.

Although the ICC has moved forward with arrest warrants, attacks against civilian infrastructure by autonomous weapons like the Shahed-136 drone complicate criminal accountability. At least three actors are potentially liable for their conduct when even such rudimentary LAWS are deployed in conflict. Complications arise for accountability with respect to each actor’s conduct and role. The first is the most proximate operator who launched the system knowing that civilian objects might be targeted, yet the operator may be shielded because domestic criminal justice rarely implicates the lowest in the chain of command. The second actor, covered by the ICC arrest warrants, sits at the very top of the chain — the one who issued orders to attack while either purposely, knowingly, or recklessly targeting civilian objects. Finally, the third actor or actors are the designers and programmers of LAWS who were responsible for their integration into military operations, especially if they knowingly or recklessly allowed the systems to target civilian objects or non-combatants. For each level or actor, the issue of criminal responsibility is complicated by technical, socio-technical, and governance accountability problems, as no one individual may end up understanding the weapon system well enough to be responsible.

With the benefit of actual ICC arrest warrants founded on evidence disclosed to the public, it appears that command responsibility could serve as a strong starting point for the application of international criminal law to certain acts and state behavior associated with the deployment of LAWS. Command responsibility is especially pertinent in cases where commanders knew or should have known that an individual under their command planned to commit a crime yet failed to take action to prevent it or did not punish the perpetrator after the fact.

Holding designers, operators, and commanders properly accountable for the use and ultimate effects of LAWS would require states to agree on broader individual and corporate accountability mechanisms. The narrower issue of international criminal responsibility in the cases of the Russian high command concerns the use of autonomous weapons to commit war crimes and inhumane acts by causing excessive incidental harm to civilians. States and international organizations should fix the miserable track record of the ICC when it comes to the execution of its arrest warrants, as seen by Mongolia’s failure to apprehend President Vladimir Putin during a state visit despite the reasonable grounds for allegations of war crimes by him and the state’s obligations under the Rome Statute.

Conclusion: A Long Road Ahead for Accountability

The critical moment of a decision to kill should be monitored to protect human dignity, assess the development and deployment of AI in autonomous weapon systems, and punish those who are responsible for international crimes. States and weapons manufacturers won’t enact such protective measures on their own.

As states invest increasingly larger portions of their GDP into the development of autonomous weapon systems, legal frameworks regulating remote attacks without human control should include legally binding obligations to monitor and assess all destruction of civilian objects or killings of non-combatants to prevent any violations of the right to life.

Overall, the development and deployment of AI-assisted autonomous weapon systems presents a need to reevaluate international criminal law and the law of armed conflict. Although the CCW’s Guiding Principles lay the foundation for how current international legal rules might offer some restraint and protection, vast disagreements among states indicate that new approaches should seek to account for and prevent the collateral damage produced by the deployment of LAWS. The Martens Clause is an important and currently undervalued aspect of the law of armed conflict that should be increasingly leveraged to keep humanity in decision-making roles over lethal decisions. To effectively promote and protect human rights against abuses due to the development and use of autonomous weapon systems by any state, military-industrial complex, or non-state actor, developments of international criminal law should be bolstered to take all collateral damage, including violations of international humanitarian law, into account. Only then will international law adequately deter terrible crimes and heal survivors.

Miron Sergeev is a second year J.D. Candidate and Conwell Scholar at Temple University Beasley School of Law. His interests span international law, trial advocacy, and corporate governance

This blog is a part of iLIT’s student blog series. Each year, iLIT hosts a summer research assistant program, during which students may author a blog post on a topic of their choosing at the intersection of law, policy, and technology. You can read more student blog posts and other iLIT publications here.