– Puja Upadhyay

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Family Court in Philadelphia transitioned to online in mid-2020 and has largely remained online since then. The group arguably most affected by the transition to online was unrepresented people, who constitute the majority of Family Court litigants.

Even before the pandemic, the process for bringing a case in Family Court was complex, but the complexity was intensified with the transition to online. While there were some benefits to the new format, there were also new barriers to successful participation, including having an adequate internet connection, a quiet space without distractions, the required technology, and so on.

However, some Family Court judges have indicated their interest in holding hearings online for some matters even after there is no longer a health risk. Given the new virtual environment, our work as part of the Access to Justice Clinic this semester was to better understand, and find ways to improve, the online Family Court experience for unrepresented litigants.

Most of our work this semester focused on gathering information about the shift to online – specifically, the biggest challenges unrepresented litigants (and practitioners) were facing, and the solutions that they hoped to see in response. Esteban Rodriguez, Ross Wiech and I felt it was important to gather a range of perspectives, and to do so with enough depth that we would be able to gain meaningful insights for our work. To that end, we relied primarily on one-on-one interviews with family law attorneys, Temple Law students participating in family law clinic, and of course, unrepresented litigants themselves. To get the fullest picture of navigating Family Court online, we also observed several Family Court hearings to see first-hand how unrepresented litigants were faring.

We also took stock of the guidance that is already available online for unrepresented litigants. For instance, Philadelphia Legal Assistance (PLA) has several webpages about navigating online Family Court and explaining the relevant law. The Philadelphia Bar Association also developed several in-depth brochures on navigating each type of matter in Family Court during COVID-19. There were also many general resources about how to prepare for a court hearing online.

However, based on our interviews and court observations, we identified a gap in the resources that were available to pro se litigants. While there is a lot of useful information available, it is spread across multiple different websites and formats. Additionally, there is relatively little guidance about participating in an online Family Court hearing, specifically in Philadelphia. Our conversations revealed that there were several tips and tricks for navigating Family Court in Philadelphia that were well known to people familiar with the system, but that were not clearly articulated in public resources.

Our goal became to create resources that would give pro se litigants a sense of what to expect at online Family Court hearings in Philadelphia. Unrepresented litigants are already juggling multiple responsibilities. Without a grasp on what to expect at an online Family Court hearing on a very basic level, they are already one step behind. Focusing on practical guidance rather than legal arguments, we consolidated the advice from our conversations, observations, and the various resources spread across multiple channels, into two “portable” PDF flyers that could easily be attached to an email or even used as a physical handout. Additionally, to dispel any confusion over what it looks like to participate in an online hearing, we created two short explainer videos that demonstrate what it looks like to join a Family Court hearing on the Court’s chosen video conferencing platform, RingCentral.

We hope that these resources will help to level the playing field for unrepresented litigants. While the transition to online has improved access to justice in some ways, it has also severely limited it in others. With luck, our contribution will help unrepresented litigants feel at least somewhat more confident when they click into their Family Court hearing link.

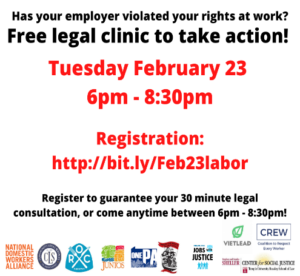

In December, CREW held their first Zoom legal clinic. I worked to organize students to help with intake. The goal of the clinic was to both educate workers and ensure enforcement against employers who are violating the laws. Before the clinic, OnePA and Community Legal Services led trainings to teach us specifically about Philadelphia’s worker protection laws and how to work with potential clients coming from CREW’s member organizations. The clinic Zoom was set up such that organizers from CREW held Know-Your-Rights trainings in the main room, while the law students and other organizers met with workers individually in breakout rooms. Volunteer lawyers were available to field questions from the individual meetings and plan out next steps.

In December, CREW held their first Zoom legal clinic. I worked to organize students to help with intake. The goal of the clinic was to both educate workers and ensure enforcement against employers who are violating the laws. Before the clinic, OnePA and Community Legal Services led trainings to teach us specifically about Philadelphia’s worker protection laws and how to work with potential clients coming from CREW’s member organizations. The clinic Zoom was set up such that organizers from CREW held Know-Your-Rights trainings in the main room, while the law students and other organizers met with workers individually in breakout rooms. Volunteer lawyers were available to field questions from the individual meetings and plan out next steps.