Ellie Holzman ’23

The Systemic Justice Clinic was an incredibly valuable experience for me. Both the seminar and the clinic project taught me a lot about how to integrate what you learn in the classroom into projects that you are working on. Professor Sibley is an incredible person and professor and I feel extremely honored to have been able to spend so much time learning from and with her. The discussion we had in the seminar were engaging and meaningful, and allowed me to think about the criminal legal system in ways that I had not previously. The clinic project was a great opportunity to put thought into practice, and I really appreciated the opportunity to have a real impact. Not only did I learn a lot about our topic substantively, but I also gained invaluable practical skills pertaining to communication, professionalism, and collaboration that I surely will take with me into my post-graduate experiences.

Luis Rodriguez ‘23

This is probably one of the most important classes/clinics at Temple. In this clinic, we spent some time looking at the philosophy surrounding our criminal justice system and incarceration but more time discussing the systemic mechanism that exists to put a lot of people in contact with the criminal system. The readings and discussions were geared towards getting us to think about how the criminal system affects us and our communities in ways that introduction to criminal law does not cover. This clinic opened my eyes to so many issues, and I am a better person and future lawyer for taking it. I wish to have this feeling with more classes. Take this clinic.

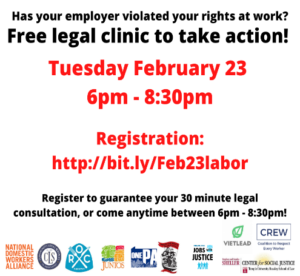

In December, CREW held their first Zoom legal clinic. I worked to organize students to help with intake. The goal of the clinic was to both educate workers and ensure enforcement against employers who are violating the laws. Before the clinic, OnePA and Community Legal Services led trainings to teach us specifically about Philadelphia’s worker protection laws and how to work with potential clients coming from CREW’s member organizations. The clinic Zoom was set up such that organizers from CREW held Know-Your-Rights trainings in the main room, while the law students and other organizers met with workers individually in breakout rooms. Volunteer lawyers were available to field questions from the individual meetings and plan out next steps.

In December, CREW held their first Zoom legal clinic. I worked to organize students to help with intake. The goal of the clinic was to both educate workers and ensure enforcement against employers who are violating the laws. Before the clinic, OnePA and Community Legal Services led trainings to teach us specifically about Philadelphia’s worker protection laws and how to work with potential clients coming from CREW’s member organizations. The clinic Zoom was set up such that organizers from CREW held Know-Your-Rights trainings in the main room, while the law students and other organizers met with workers individually in breakout rooms. Volunteer lawyers were available to field questions from the individual meetings and plan out next steps.