For years, Berks County has allowed Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to use a county detention facility to confine immigrant families and children. The arrangement has been lucrative for the County, but controversial among immigrants and immigrant advocates, who argue that secure detention of immigrant families is inappropriate and harmful.

Despite the controversy, the County Commissioners voted 2-1 in February to support an ICE proposal to expand bed space at the Center. (The Commissioners’ letter of support is here.) The Commissioners acted without public discussion and without revealing the content of the proposal that they had decided to support.

Make the Road PA and other plaintiffs, represented by the Sheller Center and co-counsel, sued the County for violating the Sunshine Act. That PA laws requires that public agencies hold their deliberations in public, and provide a reasonable opportunity for public comment on proposed action. How, the plaintiffs asked, could they provide meaningful comments on a proposal that was kept secret from them?

On June 7, at a hearing attended by Make the Road and community members, the Berks County Court of Common Pleas overruled the County’s preliminary objections and allowed the case to proceed. It is being handled by the Social Justice Lawyering Clinic, along with partners at Syrena Law, Free Migration Project, Aldea, and Al Otro Lado.

For news reports on the ruling, see our News and Publications page.

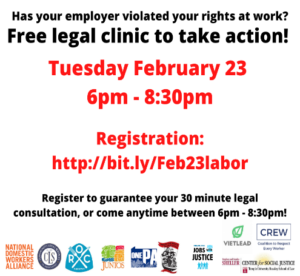

In December, CREW held their first Zoom legal clinic. I worked to organize students to help with intake. The goal of the clinic was to both educate workers and ensure enforcement against employers who are violating the laws. Before the clinic, OnePA and Community Legal Services led trainings to teach us specifically about Philadelphia’s worker protection laws and how to work with potential clients coming from CREW’s member organizations. The clinic Zoom was set up such that organizers from CREW held Know-Your-Rights trainings in the main room, while the law students and other organizers met with workers individually in breakout rooms. Volunteer lawyers were available to field questions from the individual meetings and plan out next steps.

In December, CREW held their first Zoom legal clinic. I worked to organize students to help with intake. The goal of the clinic was to both educate workers and ensure enforcement against employers who are violating the laws. Before the clinic, OnePA and Community Legal Services led trainings to teach us specifically about Philadelphia’s worker protection laws and how to work with potential clients coming from CREW’s member organizations. The clinic Zoom was set up such that organizers from CREW held Know-Your-Rights trainings in the main room, while the law students and other organizers met with workers individually in breakout rooms. Volunteer lawyers were available to field questions from the individual meetings and plan out next steps.